Argh,

I don't know if I can address all the points but there are several notable claims that need to be addressed.

- "If it's moving when you measure, it's dynamic. If it's standing still when you measure it, it's static."

We're not talking about measuring; we're talking about the factors that influence dynamic response.

When we talk about "inertia" in the piano, we're really talking about the "moment of inertia" defined as the tendency of an object to resist changes in the state of rotational motion. The MOI is calculated as I = ∑(m r²), where I is the MOI, m is the point mass, r is the distance from the axis of rotation. They are, for practical purposes, "static measurements". The MOI can be thought of as the characteristics (measurable) of an object that contribute to it's resistance to changes in rotational motion (acceleration). But they are data inputs that affect the dynamic response of the action. If we increase the mass, we increase the MOI, if we increase the r distance, we also increase the MOI. That will always be true even if we don't want it to be.

So, let's first disabuse anyone of the notion that you can't predict inertia with static measurements. Of course, it's complicated because we are talking about different levels of acceleration (not velocity per se). Acceleration and Inertia are related but not the same. The piano, obviously, offers different levels of acceleration and the force required to accelerate an action to some desired velocity from a standstill will depend on the ultimate velocity goal. To get a rocket ship to escape earth's gravity we need a lot of force. If we are leveraging the rocket into space, we need one big lever.

So then, we have to consider F = m*a. Force equals mass times acceleration. The force required will depend on the MOI and the change in acceleration that we are targeting. Again, of course, it's complicated. The piano is played not only with different levels of acceleration, but the mass changes across the keyboard (and sometimes the leverage does too). But just because it's complicated doesn't mean that we should throw up our hands and say that nobody really knows. What we can say, to one of your earlier points, is the best laid plans won't always lead to customer satisfaction. I have customers who still love their Betsy Ross spinets. That doesn't mean I'm going to change my piano design goals.

I agree that Stanwood deserves a lot of credit for bringing this dialogue to the fore. But he's not the only one doing this. Fandrich and Rhodes, Gravagne, Rick Voit (who you mention), and others, are also concerned with action dynamics. All of them use static measurements and targets to determine the proper relationship between these components. Their way of communicating how to convert that to the various components in the piano action varies slightly but mostly overlaps. Ultimately, we must distill our dynamic target to a series of choices of static inputs. We have to choose how heavy the hammers should be given the action ratio (the product of the moment arms, as a reminder), for example. Simply knowing the MOI doesn't get you very far in executing an action. You have to translate that goal into its fundamental components, m and r.

Stanwood formulas are based on static measurements: FW, SW, BW, SWR, KR, which use weight as the means of taking those measurements. But don't think that they aren't designed at targeting a certain dynamic response and it does so consistently even if, someone may not like the choice. And there are always choices to be made. The Stanwood system can be boiled down to matching SWR to a predetermined (or calculated) SW curve in order to ensure that the given a certain r or the product of three moment arms, and the m conform with each other. We accept that there are varying levels of acceleration but even that can be narrowed down to a range. There is a minimum amount or force required to accelerate the hammer enough so that it reaches the string, and there's a maximum amount of force we can reasonably apply given the physical limits of our bodies. Our calculations of F = ma always requires us choosing a value for acceleration but again, that doesn't disqualify the method. The method accepts that there are practical (not to mention useful) limitations for analyzing the action dynamics at every possible "a" value.

It should be noted,then, that the choice, ultimately, is determined empirically. For Stanwood, that has come from collecting data over many years and extrapolating by test and response. For others like Fandrich and Rhodes "Actions to Die For", I don't know how they determined their ideal, that has remained proprietary, as far as I know. But they do come up with component recommendations and those recommendations are consistent. Gravagne has a range in which he finds things acceptable, so do I. It's not a hard ceiling or hard floor, I've certainly ventured outside that range at times. But there is a basic sweet spot which I've found can be achieved (as I've stated previously) by taking into account FW, BW, SW. Those static measurements can be used to establish proper relationships between SW and AR. Is there more to be learned? Of course there is. But that doesn't mean we don't know anything and it certainly doesn't mean that we should dismiss everything we have learned so far or feel paralyzed about making rational choices based on existing information. I'm invited to join the journey??? Please, spare me.

I can't add much more (to this entire discussion) except to say that I find the claim dubious that "...even (on) a hard blow the key will come almost to a stop part way during its descent instead of smoothly accelerating to the punching? If you had said that there is evidence that the rate of accleration changes during the key stroke based on some factor (contact with the let-off button, the friction of let-off or some such thing) I would consider that reasonable. But "almost a complete stop", define "almost complete stop". Super slow mo' gives a lot of indications of things that seem extraordinary, but let's be careful about the conclusions we draw from that view.

I posted this information simply to discuss various SW curves and ask the question as to whether adhering to one shape is necessary. I obviously don't think that it is. You have one contributor claiming there is no such thing as a SW curve. Don't know how to respond to that.

Ultimately people get to choose for themselves how to pursue this. All I can say to that is: I don't really care, do you?

.

------------------------------

David Love RPT

www.davidlovepianos.comdavidlovepianos@comcast.net415 407 8320

------------------------------

Original Message:

Sent: 09-13-2025 00:19

From: Keith Akins

Subject: SW Curves

Let me come at this a different way, since the tire balancing example didn't adequately serve to illustrate the dynamic/static difference. Several points in no particular order...

- If it's moving when you measure, it's dynamic. If it's standing still when you measure it, it's static.

- It may be possible to intuit some dynamic characteristics from static measurements -- but not all.

- We don't know what we don't know. Here's an example of what *I* didn't know until recently:

- Did you know that on even a hard blow the key will come almost to a stop part way during its descent instead of smoothly accelerating to the punching? (Here's the proof from recent super high speed video courtesy of Scott Murphy, RPT)

- So, questions that come to mind include (by way of example): a) What event or events are causing the slowdown of that key? b) How would touch sensation be different if that "bump" in the graph were earlier, later, wider or narrower? (And how would you make those changes, anyway?) Does anybody know at this point? I have some ideas about question "a)" but no idea in the world what the answers are to question "b)". But I'd like to find out. And that's one point I'd like to make: when we think we know the answers we stop asking questions.

- David Stanwood. There. I've said the name we've been dancing around with terms like "current protocols" because the main driver of current protocols is known as the Stanwood Piano Touch Design and David is the author of the series of articles in the PT Journal about New Touchweight Metrology. But the fact that a process is entangled with the name of a fellow RPT does make discussion of this topic more awkward than might otherwise be the case. In regard to which, two things:

- 1) I think David Stanwood should get the Golden Hammer Award for bringing the possibility of dealing with touch issues to a broad segment of piano technicians whereas previously the general thought was that it was a topic full of mysteries only initiates at piano factories were aware of-- much less were able to do something about. So bravo to David Stanwood!

- 2) But we make a mistake if we treat a single advancement in knowledge as having arrived at the final answer. David Stanwood opened the door to the idea of touch modification but many have simply gone through the door only to make a home just inside -- instead of continuing on a journey that is clearly called for to achieve a higher level of action touch diagnostics and modification. What should have been seen as a stepping stone has been treated by too many as the final destination.

- There have been other voices questioning the NTWM approach. One worth noting is that of engineer Rick Voit who was developing his Keyforce One touch assessment machine. He wrote a couple of articles in the Journal but I think most readers (including myself) were not able to follow the details of his mathematical formulas. But here is a table that he included in a letter he sent to me critiquing the Stanwood patent that should be comprehensible by everyone.

My hope is that people who have been stuck to the NTWM protocols will consider the possibility that in terms of understanding actual playing effort/response issues we aren't nearly there yet. There is more to be learned.

You are invited to join the journey.

Keith Akins, RPT

Piano Technologist

Original Message:

Sent: 9/12/2025 8:34:00 PM

From: David Love

Subject: RE: SW Curves

Keith Akins wrote:

"It is factual that the current static theories and protocols are inadequate for all situations and in practice do not resolve all playing effort issues. This is not a matter of personal opinion or up for debate. I am aware of a number of reports of people using the currently available protocols with the result of dissatisfied customers."

Of course it doesn't answer every situation or variation in touch and dynamics or answer questions of personal taste. Who said it did? But you, and others, seem to be suggesting that dynamic performance can't be derived from static measurements. That's just flat out wrong. Is it really necessary to explain why that is (I don't see what tire balancing has to do with it)? Take any action in which the AR is uniform across the scale. The bass will have higher "inertia" (as we're using the term--really, it's the "force required to overcome inertia at varying levels of acceleration" to be more accurate) than the treble. That's directly attributable to more mass in the hammers, and to a lesser degree to more mass in the keys in the form of more lead. That will be true every time. A choice of where that SW curve should fall depending on other factors, such as how you want the action to regulate, what kind of tonal response do you want as it relates to hammer mass, is a choice of personal taste that techs make hopefully in conjunction with their playing customers. No one system will please everyone, of course. And no one has argued that and if they are and are making claims that their system will always result in a happy customer, they are delusional (but then there is a lot of that going around).

And you're calling that a customer was "dissatisfied" with a particular outcome, scientific evidence the available protocols are not adequate after arguing that personal taste is a factor. That makes no sense. No matter what the protocols, there are choices to be made about the execution. Do you choose a lower or higher AR:SW relationship? Do you opt for a higher or lower BW? Did your choice involve a low AR which resulted in excessive key dip for the player? These choices have nothing to do with protocols. I use similar protocols every time I do an action but I sometimes make different choices. You can use the same "protocol" to produce a high inertia or low inertia action based solely on the decision you make about AR/SW relationships. I don't see how that discredits anything. Plus, you keep saying the velocity is a factor, it is not, it is acceleration--it's getting to your desired velocity that is the issue, not the velocity itself.

In response to Paul McCloud, this aspect has nothing to do with friction even though friction levels will change with more mass in the hammers. But that's a separate matter.

I have no response to Chris C other than, nice promo.

------------------------------

David Love RPT

www.davidlovepianos.com

davidlovepianos@comcast.net

415 407 8320

Original Message:

Sent: 09-12-2025 17:38

From: Keith Akins

Subject: SW Curves

I expected blowback. Just to summarize:

Using the "tire balancing" analogy, just as some tire imbalance issues are fully resolved by the "bubble balancing" procedure, so also SOME current playing effort protocols MAY be useful in SOME -- perhaps many -- situations. However...

It is factual that the current static theories and protocols are inadequate for all situations and in practice do not resolve all playing effort issues. This is not a matter of personal opinion or up for debate. I am aware of a number of reports of people using the currently available protocols with the result of dissatisfied customers.

The present situation is that we have certain theories and protocols and do what we can do. One of my concerns about the present state of the art is instead of recognizing the limitations of where we are at, I have seen an almost cult-like defense of the status quo rather than recognizing present limitations and moving toward a more scientific, physics-based dynamic approach: not only are people not measuring velocity, efficiency and latency, some seem uninterested in developing that capacity and meanwhile recognizing that our inability to make those measurements may explain much of the variability that is happening when current protocols are applied.

Keith Akins, RPT

Piano Technologist

Original Message:

Sent: 9/12/2025 2:04:00 PM

From: David Love

Subject: RE: SW Curves

I disagree with your premise, static measurements are definitely an indication of inertia. Static measurements include the action ratio and they include the mass of the object you're trying to move --since we're only operating on earth we can use weight in place of mass. Those are the two major components of inertia and those are both static measurements. If you try and slide a refrigerator across the floor, one that is empty versus one that is packed full of soft drinks, the force required to overcome a inertia will be greater for the one that weighs more. Weight is a static measurement.

Velocity, by the way is not the key component with respect to force required to overcome inertia, its acceleration. A rocket ship traveling of its own momentum, in propelled through space is not overcoming much inertia if any. To get the rocket into space is overcoming a lot--same object.

Nobody is arguing, in fact just the opposite, that balance weight is a dynamic factor. I'm not sure what that's in response to. But the static weight is a factor in perception of touch weight. You can feel the difference between a key that has a balance weight of 50 g and one that has a balance weight of 30 g. While that doesn't necessarily speak directly to the dynamics, it's not a meaningless number. My response to Tim addresses why that might be.

------------------------------

David Love RPT

www.davidlovepianos.com

davidlovepianos@comcast.net

415 407 8320

Original Message:

Sent: 09-12-2025 13:42

From: Keith Akins

Subject: SW Curves

So the deeper issue here is that all of these measurements are static in nature and static measurements do not reveal the dynamics of the key/hammer stroke in motion. As such, none of them can reliably diagnose/predict all the issues that may affect the sensation of playing effort (a more accurate term than "touchweight" -- a term which borders on voodoo physics).

Completely absent from current discussion about playing effort are terms like latency, efficiency, and velocity. There being no discussion of that last term is particularly odd since the piano is a velocity multiplication machine.

To understand what I mean by "dynamic vs. static" let's use the example of tire balancing: Tires need to be balanced or they cause unpleasant-to-dangerous vibration when the car is being driven. There is no problem when the car is parked.

There are two methods of balancing car tires: static or "bubble balancing" and dynamic a/k/a "spin balancing.

For static balancing, the tire is mounted horizontally on a device that has a 360º level or "bubble". Different weights are placed around the rim of the tire to center the bubble and then attached. This is effective for a significant number of tire imbalance scenarios that cannot be improved by a dynamic procedure. However, there are also a significant number of scenarios where a tire "balanced" by the bubble procedure will vibrate when running on the car.

In dynamic balancing, the tire is mounted vertically as in actual use on a car and then rotated at significant speed-- hence, the term "spin balancing". With this machine, imbalance is detected as the tire is in motion with 100% reliable results when the tire is placed back on the car and driven.

DW-UW/2 is a centuries-old formula for measuring the accuracy of balance scales. Applying that formula to piano actions is simply not reflective of the dynamic reality. Measuring action ration -- by whatever means -- at best can only lead to inferences about action playability.

My point for which method to measure action ratio is don't get bogged down with it. No static method is truly reflective of the dynamic reality. Instead of fooling ourselves by thinking we are being "scientific", the present reality is that successful modification of action performance involves an appreciation of basic physics and a good deal of intuition (an idea long expressed by our respected former colleague by the name of Anderson from California whose first name I can't remember).

The ability to measure the dynamics of playing effort is on the horizon. Meanwhile, we have to manage with our present abilities.

Keith Akins, RPT

Piano Technologist

Original Message:

Sent: 9/11/2025 1:00:00 AM

From: David Love

Subject: SW Curves

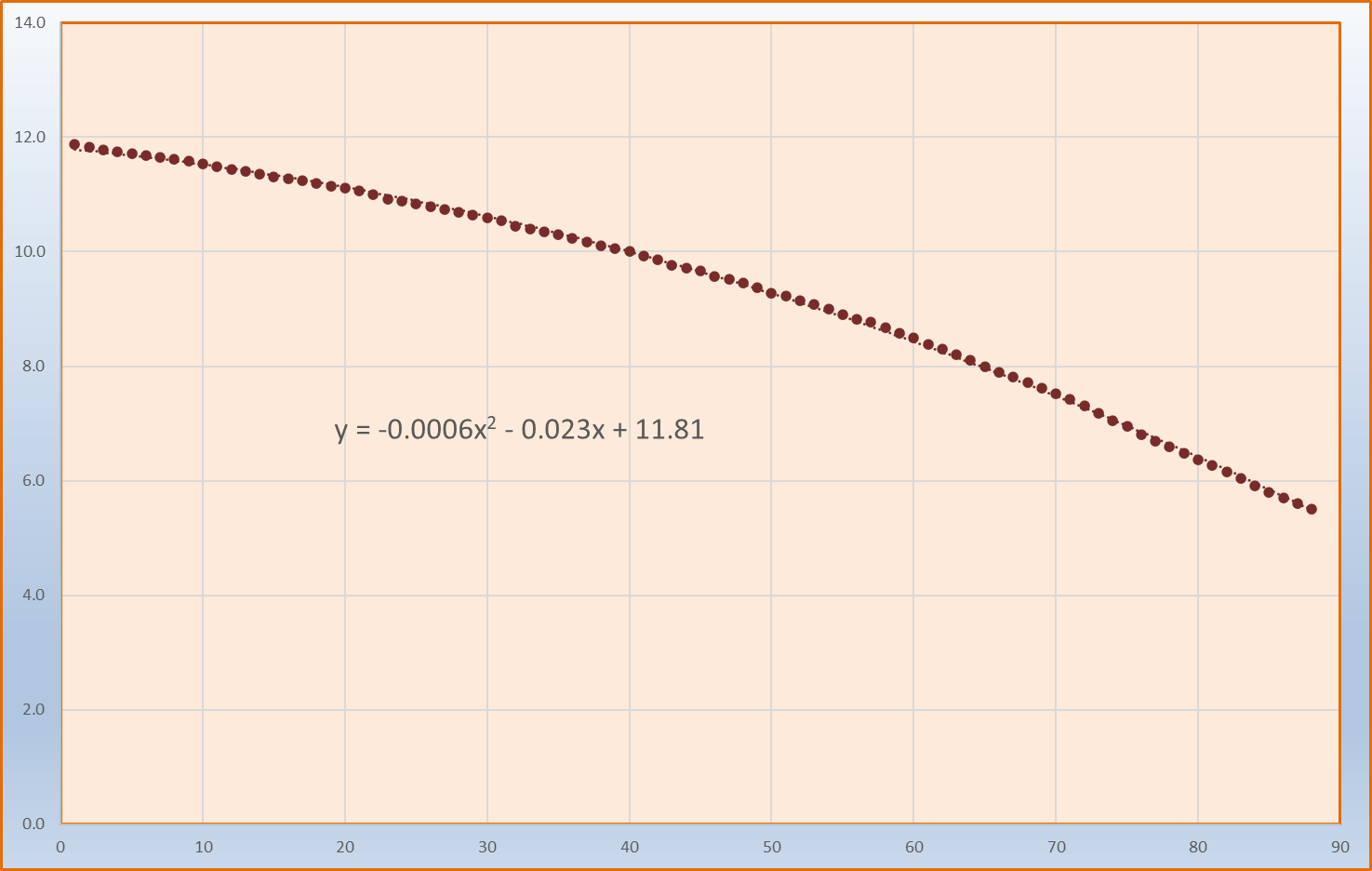

We are used to seeing SW curves that look something like this (top graph). This is a 2nd degree polynomial that corresponds to the equation on the chart. This would be a typical Stanwood style curve, one that is often targeted, though at various values, usually determined by the accompanying AR.

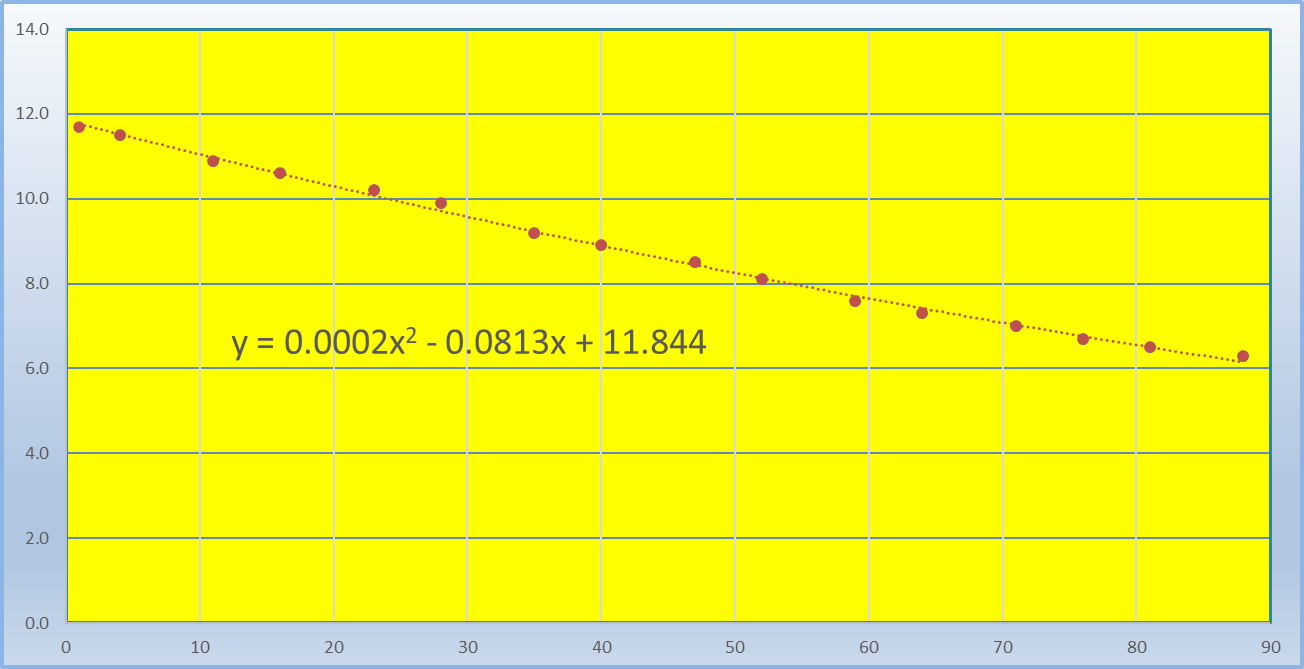

However, I often see hammer sets that come out of the box more like this (lower graph) which is also a 2nd degree polynomial (equation on chart). The difference here is the positive value of the first coefficient--note that the curve dips in the middle slightly. In the graph below pay attention to the small dotted "trendline" which is derived from the larger dots representing samples taken through the set. (BTW this is the weight curve of a set of Renner Blue Points Gr3)

So the question posed to me by someone I'm helping with this is: What shape should we target? Is it assumed that the style of curve pictured in the first graph is one should be copied no matter what the set itself suggests? Or should we go with what we are given out of the box and simply smooth the curve in whatever shape the set suggests or conforms to? Why, and what will be the difference?

My own practice is to accept what the set gives me mostly because I can't find a compelling reason not to. Which isn't to say there are no differences.

One difference is that, all things being equal, i.e. AR and Balance weight target, the lower SW values will always yield lower FWs and lower net inertia (FWs being a consequence, not a factor in that lower inertia). The reason for that is because the inertia is determined primarily by the AR:SW relationship (as has been discussed). This is the same principle that will always yield lower inertia in the treble than in the bass. And given ARs that are equivalent the set with lower SW values will have lower inertia. In the second graph, then, the midrange of that piano will have lower inertia than the upper graph (again, assuming AR's are equivalent).

Is there evidence to support that one is preferable to the other? For the most part, action balancing is very personal thing dependent on the player's taste and, perhaps, skill. Some will like lower inertia (and BW) some will like it higher. I make no presumptions about what people will like, all actions I do, I set to a default setting of a specific BW and inertia levels determined by targeted FW specs which combined with AR will yield a predictable level of inertia (yes, you can use static measurements to determine inertia). But I ultimately let the player decide what they like and if they decide they want it lower or higher inertia or BW, I offer that service. Many players FWIW, don't know what they like but everyone wants predictability which means uniformity. Sometimes it takes a player awhile to determine what is ideal for them.

Anyway, just food for thought, not expecting an answer (because I don't really think there is an answer). The purpose is more to point out that we often fall into certain habits of working. Sometimes there is a basis for it, sometimes, it's just that, a habit.

But wait, what about regulation, you say!? That's always dependent on AR but is a question for another day.

------------------------------

David Love RPT

www.davidlovepianos.com

davidlovepianos@comcast.net

415 407 8320

------------------------------